Why Your Brain Won't Let Go (of Clutter)

Jun 06, 2025

Have you ever found yourself staring at a closet full of clothes you never wear or a kitchen overflowing with gadgets you never use, yet feeling unable to part with any of them? You're not alone. Many of us struggle with letting go of clutter, and the reasons go far beyond simple sentimentality or a lack of organizational skills. It's deeply rooted in the psychology of decision-making and the way our brains are wired.

In the late 1970s, Daniel Kahneman (who has since won a Nobel Prize for this work) and Amos Tversky revolutionized our understanding of how we perceive gains and losses with their groundbreaking Prospect Theory. This theory sheds light on why we often make seemingly irrational decisions, like holding onto items we don't need. Their insights into human behavior have profound implications for everything from economics and marketing to personal habits and, yes, even the clutter in our homes.

If you’re bumping into roadblocks, understanding these mental mechanisms might be just what you need to empower you to overcome the emotional barriers to a clutter-free life.

So, why can't we let go of that old, unused gadget or those clothes that no longer fit? Let's find out.

Prospect Theory

Prospect theory is about how we make decisions when we're faced with uncertainty or risk. Instead of being perfectly rational (surprise), we often make decisions based on perceived gains and losses rather than actual outcomes.

It all comes down to maintaining the status quo, and we interpret gains and losses according to this status quo (our point of reference).

We tend to be risk-averse about gains relative to the status quo (meh, I’m not going to risk it—things are fine the way they are) but risk-seeking about losses relative to the status quo (I’ll do whatever it takes to keep things the way they are).

There are two parts to this- two functions used in the Prospect Theory that show where our decision-making deviates from reality.

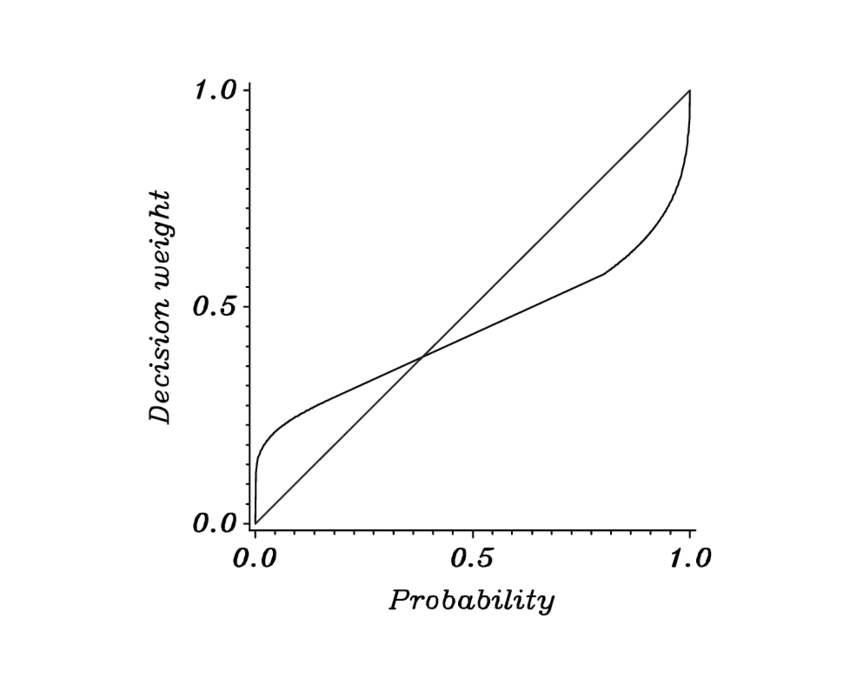

One is the Probability Weighting Function (how we weigh the probability of something happening or whether or not we see something as being likely to occur)

- Y-Axis: Represents the subjective probability (how likely you think something is).

- X-Axis: Represents the actual probability (how likely something really is).

- The diagonal line at 45 degrees represents a perfectly accurate perception (this would mean that our assessment is spot on).

Well, the rule of numbers shows that we value things like this:

Probability Weighting Function:

- The curve is above the diagonal line for low probabilities

- Overweighting Small Probabilities

- We think rare events are more likely than they really are.

- You might hesitate to get rid of those extra pots because you fear that one day you'll need exactly that pot to make a specific meal, even though this is a rare event. In reality, you rarely use those extra pots, and the likelihood of needing them all at once is quite low.)

- The curve is below the diagonal line for high probabilities.

- Underweighting Large Probabilities

- We think common events are less likely than they really are.

- You might underestimate the daily frustration and inconvenience of having a cluttered kitchen, even though the probability of it causing stress and inefficiency in your daily cooking routine is quite high.)

The other is the Value Function (how we view the value and benefit of something)

- Y-Axis: Represents the subjective value or perceived benefit (how valuable you think something is).

- X-Axis: Represents actual gains and losses (how valuable something really is).

- Origin: The center point where the x-axis meets the y-axis is the reference point (status quo).

Value Function:

- Concave for Gains:

- The curve above the x-axis (right side of the origin) bends downward.

- This means that the more you gain, the less additional value you feel. For example, gaining $100 feels great, but gaining another $100 after that doesn't feel as good as the first $100.

- Convex for Losses:

- The curve below the x-axis (left side of the origin) bends upwards.

- This means that the more you lose, the less additional pain you feel. For example, losing $100 feels bad, but losing another $100 after that doesn't feel as bad as the first $100.

- *Steeper for Losses:

- BUT, the slope of the curve for losses is steeper than for gains.

- This indicates that losses hurt more than equivalent gains feel good. For example, losing $100 feels worse than gaining $100 feels good. Or, in decluttering terms, decluttering a nice pair of shoes (even if they don’t fit anymore) feels worse than getting a new pair for your birthday feels good.

And this, ladies and gentlemen, is called Loss Aversion—that’s really what we’re here to talk about—this is why your brain won’t let go of clutter! But don’t worry—we’re going to talk about ways to work around this, too, so stick around.

In a nutshell, we tend to overvalue small gains and undervalue large gains, feel losses more sharply than equivalent gains, and misjudge the likelihood of events happening. So, that’s where we are.

Loss Aversion

Loss Aversion - is a cognitive bias that refers to our tendency to prefer avoiding losses over acquiring equivalent gains.

In other words, the displeasure we experience from losing something 😟 is generally stronger than the pleasure we feel from gaining something 🙂 of equal value.

I was talking about this with Matt the other day. He brought up how exciting it would be if someone gifted you a vacation. Wouldn’t that be amazing?! A free vacation, including flights and food…all for your enjoyment.

Compare that to someone giving you cash to go book your own vacation…now it somehow feels less good. It’s still nice…but now you have to go through the process of owning a bunch of cash and letting it all go toward the vacation.

That’s one reason why gift cards are generally a more popular option than giving cash. People will often not use the cash to splurge on themselves because of the sensation of loss.

Think about it this way: what would you do to keep from losing your home? People have done some pretty aggressive things to hold onto what they have. Would you beg? Would you forge a document? Just once? Just one tiny little signature to keep from losing everything?

Maybe, maybe not. You might entertain the thought… But what about upgrading to a house twice the value of yours? Would you beg for that? Meh, we’re fine the way we are. Would you entertain the thought of forging a document? Probably not. It’s not worth the risk of prison.

Now, I’m not saying you would do either, but I’m sure you can feel the emotional difference between the two decisions.

Loss Aversion can significantly impact our decision-making process regarding our belongings, making it difficult to let go of items we no longer use or need. We fear the perceived loss associated with getting rid of something, even if it holds little practical value or really serves no purpose in our lives.

Brain imaging studies have shown that the emotional response to losses is processed in the same areas of the brain associated with pain.

Endowment Effect

The Prospect Theory laid the foundation for understanding the endowment effect, which is closely related to loss aversion. The endowment effect is something I’ve brought up many times in my channel and in my course, Clutter Cure because it’s literally a psychological bias for the things we own.

The endowment effect is a psychological bias where we attribute more value to something simply because we own it.

For example, in one study, subjects were randomly assigned to be buyers or sellers. Sellers were given a coffee mug valued at $6 and were asked whether they were willing to sell their mugs at a range of prices between $0.25 and $9.25. Buyers were not given mugs and were asked whether they were willing to buy mugs from the sellers at the same range of prices.

The results were that sellers consistently valued the mugs higher ($7.12 on average) than the value the buyers ($2.87) were willing to pay for them. In some cases, the sellers preferred to keep their coffee cups rather than sell them.

People are often unwilling to give up what they have to get something else that they might otherwise prefer because a loss has a greater psychological impact than a gain.

Now, let’s dive back into how we can apply the principles of Prospect Theory and Loss Aversion to our lives, specifically in the context of decluttering.

Key Points of Loss Aversion:

- Psychological Impact: People experience stronger emotional reactions to losses than to gains. For example, losing $100 typically feels worse than finding $100 feels good.

- Decision Making: Loss aversion can heavily influence decisions. Individuals might avoid taking risks, even if the potential benefits outweigh the risks because the fear of potential loss is so significant.

- Framing Effect: How choices are presented or framed can affect decisions. A scenario framed in terms of potential losses can lead to different choices compared to the same scenario framed in terms of potential gains.

- Endowment Effect: People tend to value what they own more highly than what they do not own, which can be attributed to loss aversion. This means they are more reluctant to give up something they own, even if they are offered something of higher value in return.

Overcoming Loss Aversion:

- Reframing: Presenting choices in a way that emphasizes gains rather than losses can help mitigate the effects of loss aversion. (Realizing the downside of holding onto these things, such as an abundance of clutter, stress, and an overall sense of overwhelm, can help you reframe your perception of what constitutes a loss.)

- Small Wins: Encouraging people to focus on small, frequent gains can help them feel less averse to potential losses.

- Education and Awareness: Helping people understand the concept of loss aversion and how it influences their decisions can lead to more rational decision-making.